Learning Outcomes Assessment, Make It Real

You probably saw it in the Chronicle of Higher Education (October 27, 2009) in the comments of George Kuh, director of the National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment. He makes several observations that align with our experience, reading, and thinking. He notes, for instance, that “what we want is for assessment to become a public, shared responsibility, so there should be departmental leadership” (paragraph 14).

He also notes that lots of places have developed outcomes, however:

“What’s still disconcerting is that I don’t see a lot of evidence of closing the loop. There’s a lot of data around, there’s some evidence it’s being used in a variety of ways, but we still don’t know if that information is being transferred in such a way as to change practices for the better. That’s still the place where we’re falling short” (paragraph 6).

Part of the reason closing the loop is so difficult is that outcomes assessment remains removed from what faculty do in their classrooms. (There’s a nice piece in Inside Higher Ed today on this, but this post is already too long.) So what we’ve learned that tends to work better and is generally most practical is to put the focus on what faculty are already doing.

Peter Ewell, the VP of The National Center for Higher Education Management Systems, came to a similar conclusion that resonates with our experience and suggests a strategy for making outcomes assessment truly “practical” or “functional” for closing the loop. Lamenting the failure of more than 10 years of the assessment reform in helping institutions and faculty close the loop, Ewell says:

“I have learned two additional lessons about the slippery matter of articulating abilities. First, it’s more useful to start with the actual practice of the ability than with the stated outcome. Phrases like ‘intellectual agility’ have great charm, but mean little in the absence of an actual student performance that might demonstrate them. To construct assessment techniques, formal assessment design, as described in the textbooks, demands ever more detailed verbal specifications of the outcomes or competencies to be developed. But it is often more helpful to go the other way. Given a broad general descriptor like ‘intellectual agility,’ can you imagine a very concrete situation in which somebody might display this ability, and how they might actually behave? Better still, can you quickly specify the parameters of an assignment or problem that might demand a particular level of ability for access? The performance that the student exhibits on the assessment is the definition of the ability itself; the ability has no independent existence” (pp. 6, 2004, General Education and the Assessment Reform Agenda).

We’ve worked with a couple of dozen programs here at WSU (and more than a few elsewhere) and found that starting with the real and embedded assignments faculty use is an effective way to approach outcomes assessment. It helps programs refine and make concrete their understanding of outcomes in the context of their own teaching. It helps them close the loop as reflected in their own assignment design.

Given the ever increasing pressure to demonstrate outcomes educators all face, and in the interests on building outcomes assessment systems in the day-to-day work in which faculty are already engaged, starting with activities faculty already use is what will give us the best, well, outcome😉

Nominialism and the Recursive Curriculum

Traditional grading is nominalist. It assumes learning is sequential, that learners build their understanding in nicely layered base of segmented factoids supporting an increasingly more advanced understanding of the content that presages critical reasoning.

Curriculum is similarly organized into nicely boxed units of content, and each boxed presentation of content is followed by a test or quiz to verify they have learned the requisite basics.

We teach a chapter, test, grade. Bloom’s taxonomy is often evoked to support an understanding of basics needed before learners can think critically. But this vision of teaching, learning, and testing conflates Bloom’s taxonomy with an imagined learning chronology (something Bloom distinctly disavowed). But research clearly counters this model. Knowing, remembering, and thinking critically are in important ways very different phenomena.

Perhaps the most compelling example of this is the “Private Universe” project from Rutgers. In a wonderful longitudinal study, the Rutgers researchers observe (visible in the linked video) young children who essentially invent multiplication because they need to to solve a presenting problem. The authors observe:

“Research shows that children formulate extraordinarily interesting and complex mathematical ideas, even at a very young age. The Private Universe Project in Mathematics demonstrates and honors the power and sophistication of these ideas, and explores how mathematics teaching can be structured to resonate with children’s sophisticated thinking.”

It is possible, of course, that the assumptions about learning are unrelated to the organizations of tests and terms, but that is another discussion.

Regardless, learning is not linear.

Learners construct schema and learn in different ways, associating what we are learning to what we have learned from our unique experiences, reading, and dispositions. Subsequently, what we learn from the linear presentation of content by chapter and by test resembles only faintly what was presented, however brilliantly lectured or organized.

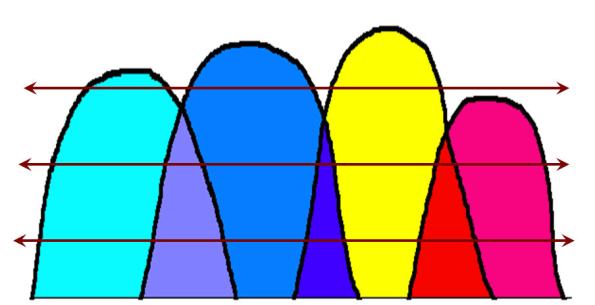

There are many reasons, perhaps none so important as the fact that learning is recursive. A better visual representation of curriculum aligned with the way people actually learn suggests that deeper learning and more sophisticated connections are made as learners continue to explore problems or answer questions. In a recursive approach to curriculum design, the big questions shape and guide the learning. In the picture below, each attempt to address the question or solve the problem results in a deeper penetration into a body of knowledge where the boundaries between content, as one goes deeper, more fully overlap and blur.

Recursive Curriculum

The implications for grading suggest the criteria for performance should correspond to a deepening understanding and the ability to integrate and apply knowledge rather than count and reward a superficial sequential memorizing of content. More importantly, a model of grading that corresponds to the way people learn need also recognize that learning happens over time.

In that regard, the need to explore ePortfolios and to cultivate learners’ metacognition (reflection) of their own deepening understanding becomes clear.

Finally, the preceding is prelude. It is important to recognize that research confirms that learning is profoundly social and enriched by feedback. It is to that end that we encourage models of assessment that empower learners to harvest feedback from multiple sources.

Relinquishing Assessment, The Consequences

I noted this morning the AAC&U meeting where they focus on ePortfolios and rubric based assessment:

AAC&U anticipates the complaint:

“What is the cost—in money, time, and energy—of implementing comprehensive e-portfolio assessment of student learning?”

They counter, “What are the costs of not doing it?”

We’re seeing that cost daily. More than a year ago Boeing announced their initiative to rate institutions based upon the performance of the employees they hired. Even as our institutions wrestle with accountability and accreditation and strive to meet the expectations of stakeholders beyond the walls of the academy, key stakeholders of higher education are not waiting idly. Boeing, in order to inform their own recruiting, hiring, and research partnering has mapped their internal employee evaluation data to develop a ranking system tracking employees back to the college programs from which they graduated (Baskin, 2008). With 160,000 employees working around the globe, a significant part of their rationale is that they already spend about $100,000 on course work and supplemental training for employees. It is also not a coincidence that their senior vice president, Richard D. Stephens, was a member of Margaret Spellings’ Commission on the Future of Higher Education, a panel formed by the U.S. Education Secretary in 2005 to determine if investment in higher education delivers an acceptable return. Stephens said that his experience sitting through many meetings of the commission “listening to long discourses by education professionals about ways to lower the cost and improve the effectiveness of college” helped him realize that Boeing “would have to take action on its own” (in Baskin, para. 8).

Boeing reported willingness to share their findings “in an effort to help [colleges] improve themselves” (in Baskin, para. 11). More specifically, the effort is, as Boeing reports, “really about improving the dialogue on curriculum, performance, and how we can build a stronger relationship between the colleges, universities, and us, because, ultimately, their students become our employees” (in Baskin, para. 12). Boeing says, further, that they need “more than just subjective information” for evaluating the colleges that Boeing visits to recruit and hire (in Baskin, paragraph 4). And there is a flip side that pertains to the challenge to educators. “The Boeing project also will invite greater examination of its employee-evaluation criteria, which currently include both technical and nontechnical skills. Carol Geary Schneider, president of the Association of American Colleges and Universities, says, “Ideally, the company’s measures will reflect a wide-ranging definition of worker success and may thereby spark greater appreciation of well-rounded students” (in Baskin, para. 19). As for professional skills like teamwork and communication, Schneider observes, “Employers are much better able to call students’ attention to the importance… than their deans are” (in Baskin, para. 22).

One question this trend surfaces, when education relinquishes responsibility for authentic assessment (which is not the subjective stuff of grades), how long before credentialing follows?

Online Response Rates, Myths and Misdirection

Concerns about the generally lower response rates in online student evaluations often eclipse the need to focus on gathering information that is useful—and then using it in productive ways.

I was reminded of this point when reading a piece in the Chronicle of Higher Education on October 5, 2009 pointing to the tendency to project too much on response rates in survey assessment:

http://chronicle.com/article/High-Response-Rates-Dont/48642/?sid=at&utm_source=at&utm_medium=en

A little mentioned flip side has emerged in discussion on The American Evaluation Association list, where evaluation experts have debated the extent to which coerced responses—such as proctored, required, or even student evaluations baited with extra credit—compromise the validity and send the wrong message.

In our own studies here at WSU, where we followed up with non-respondents, led us to conclude that response rates were a kind of de facto measure of student engagement. Many students felt—often rightly—that their opinions won’t have much impact.

Conversely, when faculty convey that student opinions matter to them, we see an increase in the responses rate. And that appears to be more likely when leadership in a program demonstrate their engagement in student evaluations. Here’s the link to that study:

http://innovateonline.info/INDEX.PHP?view=article&id=301

In addition, we’ve compared paper based evaluations with online evaluations and, though response rates vary, distribution of ratings does not, which appears to pop another myth. Extra credit raises response rates about 5%, but that no doubt introduces yet another kind of bias. Making the online form available longer does not appear to matter. We have a few other observations and some discussion at:

http://wsuctlt.wordpress.com/?s=response+rates

There are other studies that confirm our own studies. Berkeley did a study http://hrweb.berkeley.edu/ldp/05courseevaluation.doc

Another resource comes from The University of Minnesota that reports, as we have, that there is no significant difference between paper-based near 100% participation and the online method with participation as low as 60%. http://net.educause.edu/E06/Program/9155?PRODUCT_CODE=E06/SESS009

If you have about 40 minutes, Michael Theall, an expert on student evaluations, presents a good summary of many studies that essentially echo the preceding points. In addition, he makes a strong case for the potential utility of student evaluations—when done well and used appropriately. His Do Student Perceptions Really Matter Webinar can be found at: http://vimeo.com/6932313

It’s that qualification—done well and used appropriately–that prompts this post, though. Response rates and even validity matter very little if student evaluation results are used in essentially unproductive ways like ranking and comparing faculty. I’ve not yet seen an instrument that really represents the kind of data (ordinal) that justifies using statistical measures of central tendency. And whether it is a comparison of faculty or of the institutions they work for, when has a comparison ever provided useful insight for making improvements?